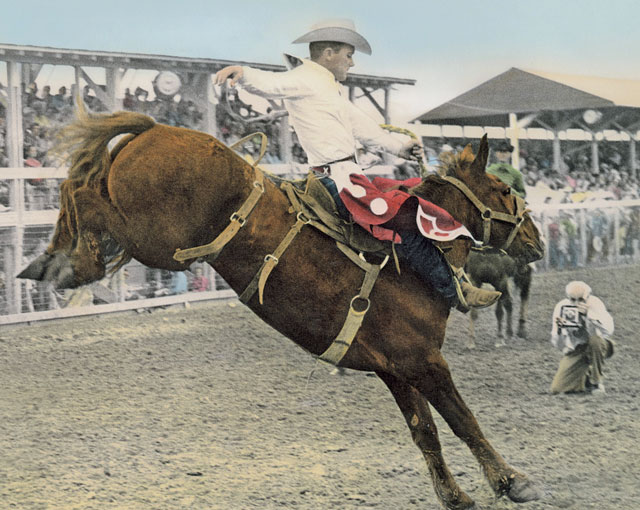

Because of a box of western magazines, and his dislike of cows, Lyle Smith became a saddle bronc rider. The Canada native now living in Reno, Nev., competed at four National Finals Rodeos and finished in the top ten in the world six times, making his mark in the rodeo industry. He was born in 1930 to George and Louise (Reuther) Smith, the third of eight children, on a farm near Donalda, Alberta.

When he was seven years old, his dad died, leaving his mom with eight mouths to feed and not much to put on the table. The family milked cows, raised chickens and gardened, to make it through. His older brothers milked three cows, morning and night, “so I grew up hating cows,” Lyle said. “I couldn’t get away fast enough from that farm.”

He attended a country school that went through the ninth grade, and when it was time to go to high school, he couldn’t go. There was no school busing in that district, and the family couldn’t afford to make the sixteen mile trip to Donalda High School.

So he went to work for a rancher named Herman Linder, and the trajectory of his life changed.

Linder, himself a world champion bronc rider in his time, had a box of Hoof and Horns and Western Horseman magazines in the attic where Lyle slept. In his spare time, he would read them. “I read about Jerry Ambler, Carl Olson, and others who were world champions, and I thought to myself, ‘that’s the life for me.’”

So he gave Linder two weeks’ notice, then went home. His cousin, Lawrence Bruce, had bucking horses, and invited Lyle over to try some out for Harry Vold, who was scouting prospects for Leo Kramer, a stock contractor from Montana. Lyle got on four horses that day and bucked off three of them.

It was 1948, and he helped Lawrence as they drove horses to a rodeo in Holden, Alberta, where Lawrence was taking saddle broncs. Lyle entered the amateur bronc riding and won fourth place and ten dollars. His mind was made up. “That made me think rodeoing would be a way to get away from the farm and working for farmers,” he said. He entered the amateur bronc riding at other stampedes, which was what rodeos were called in Canada at that time.

In 1949, his big win came in St. Paul, Alberta, over the fourth of July. He won first place and $275 and used it to buy a Hamley association saddle. Prior to that, he had borrowed one from whoever he could.

The next few years, he competed in the amateur bronc riding at stampedes across Canada, wining here and there. His skills improved in 1951 when he worked for Lawrence, the father of Duane and Winston. He helped build a poplar rail and post arena, and the boys would try out horses and practice each day. “I got to riding better,” he said. He competed again across Canada but added a few stops in the U.S., too, including Lewiston, Idaho, and Pendleton, Ore. That same year, he got his Rodeo Cowboys Association (RCA) card.

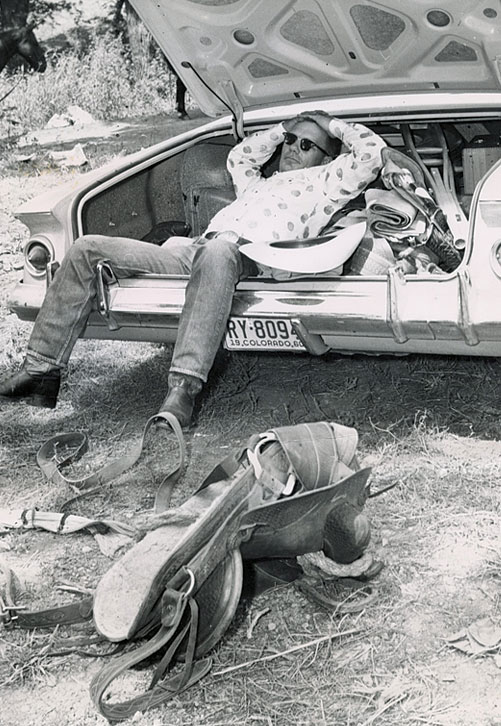

Rodeo wasn’t his main income; he worked on an oil well drilling rig. He, along with the other cowboys who were short on cash, knew how to stretch their dollar, eating one meal a day and piling into the cheapest hotel rooms they could find.

It was in 1954 that his rodeo career took off. In Denver, he won fourth in the day money, a check for ninety dollars. But that was it, and Lyle was out of money. He competed at Ft. Worth, San Antonio, Houston, squeaking by on his winter earnings. Phoenix was the last of the big spring rodeos, and after Lyle rode there, he went home with Deb Copenhaver. Copenhaver, a two-time world champion, put Lyle to work on his ranch in Idaho, where he dug postholes and fenced. Deb entered him in Red Bluff, Calif. in April, where Lyle earned a fourth place day money check again. After that, he kept on winning rodeos from Vernon, Texas to Madison Square Garden in New York City, Boston Garden, and San Francisco.

The good days were here.

He rodeod all year, across the nation, from Denver to Ft. Worth, and from Baton Rouge to Oakdale, Calif. In 1957, he won $7,100 for the year and bought a brand new 1957 Chevrolet for $1,900. The next year, his annual earnings were $10,264 and he finished sixth in the world.

In 1959, he went to the first National Finals Rodeo, in Dallas, Texas, where he won a round and fourth in the average. He also was the high mark saddle bronc ride for the Finals, with a score of 187 points on a horse from Ray Kohrs, a stock contractor from California. (At that time, 210 points was the highest possible score in the roughstock; the scoring system changed to its present form of 100 points as a perfect ride in the mid 1960’s.)

The next two years, he went to the National Finals, wrapping up the 1960 season in sixth place with $11,285 in earnings, and the next year in seventh place, with $10,577 for the year. The year 1962 was the last time he would qualify for the Finals. By that time, Lyle was living in San Diego, working for rodeo cowboy Bob Robinson in a housing development. He was married with a son, and there were bills to pay. “You’ve gotta have money coming in when you’re married,” he said. “You can’t get by on one meal a day.”

He and his buddies lived in San Diego, working during the week and rodeoing on weekends. At the time, there were lots of little rodeos around the area. “It was probably the best time I had rodeoing,” he remembered.

In 1964, the job ended. He found work in Reno for a painting contractor. His rodeoing was slowing down, and in 1967, he rode his last bronc at the rodeo in Fallon, Nev., wining first place. Lyle had other priorities: his family and his work. “I was busy working, making pretty good money, and I couldn’t afford to go to a rodeo.”

He got his contractor’s license in 1971 and has been working as a painting contractor ever since.

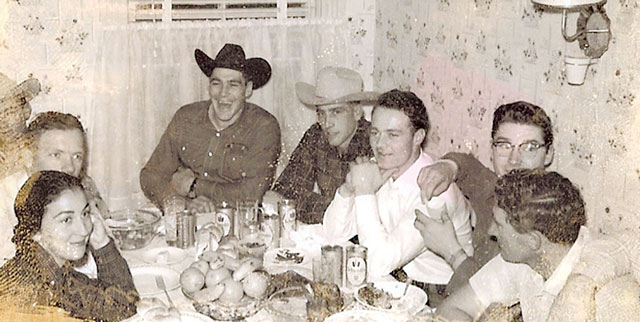

Lyle had met his wife Joan in 1958 in Boston. He and his friends were there to compete at Boston Garden, killing time during the day, walking through Johnny Walker’s western store. She had tickets for the rodeo that night, and now she had a cowboy to cheer for. Her family loved him. They were excellent cooks. When the cowboys came to Boston Garden to rodeo, they would all be invited over for a meal. “Her uncles would cook. They were really great people,” eh said. They married on April 5, 1959.

Lyle suffered a broken back in 1956 when a bronc fell over in the chute with him at the Oakdale, Calif. rodeo. He was in the hospital for twenty days, and the nurse, who was the same age as his mother, took him under her wing after his hospital stay was over. She was married to a ranch cowboy and understood his predicament, caring for him a month at her home after he got released from the hospital.

His other two serious injuries were from vehicle accidents. In 1980, he was in a car accident, breaking his right shoulder and a bone in his leg. And eleven years ago, as a pedestrian, he was hit by a car, breaking his pelvis and spending time in the intensive care unit and rehab.

The couple had a son, Chris, who was born in 1960, and who is married to his wife Seanne. Lyle and Joan have six grandkids, “every one a success and a great kid,” he said, and five great grandkids. One of his grandsons is named after him, and all of the grandsons are in the Air National Guard.

He and his son Chris still own and operate the painting contracting business, and at the young age of 89, he still goes to the office. He no longer drives; Chris picks him between 5:30 and 6 am in the summer and at 8 or 9 am in the winter. He hasn’t painted for the past five years, but he answers the phone, does paperwork, and bids jobs.

There’s still plenty to do, and he loves it. “I don’t know what I’d do if I completely stopped and sat in the house. I wouldn’t last long.”

He was admired by his peers, and still is, says his friend Herb Friedenthal, a bull rider who is ten years his junior. “He was level headed,” Herb said. “He was real popular. Everybody liked him.”

Herb acknowledged Lyle’s skill in the arena. “He was one of the best. He could ride those big old rank horses, those horses that came out of the north from Canada, Montana, the Dakotas. You would hardly ever see him hit the ground. He might not win every rodeo, but he wouldn’t get bucked off.”

Lyle loved his rodeo days. “I loved to rodeo,” he said. “I loved the guys I was with. I made friends that I’m friends with, to this day.” Since the Wrangler National Finals moved to Las Vegas in 1985, he’s missed only one year of attending the reunions held in conjunction with it.

The hardships of his childhood helped him succeed in rodeo and in life and made him tough, he believes. “Learning to make it as a rodeo cowboy got me away from the farm,” he said.

“He’s a real good guy, a real good guy,” Herb said. “And he still is.”