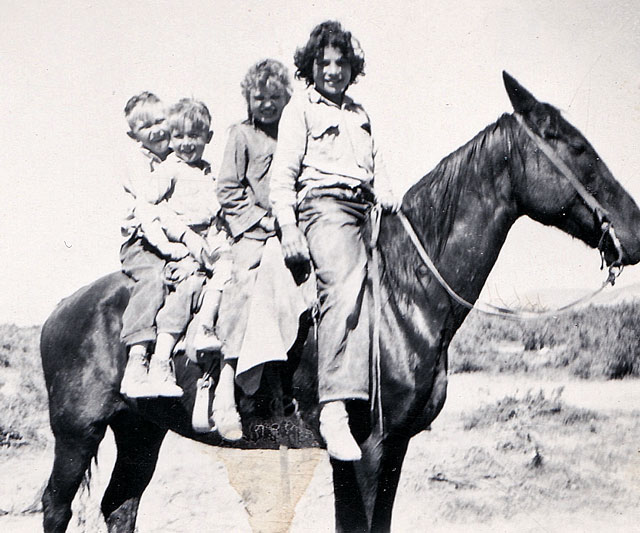

Whether it was with wild horses, barrel horses or movie horses, Sammy Thurman Brackenbury lived her life with spirit, a sense of adventure, and a shot of adrenaline. By the age of seven she was breaking mustangs with her dad and selling them.

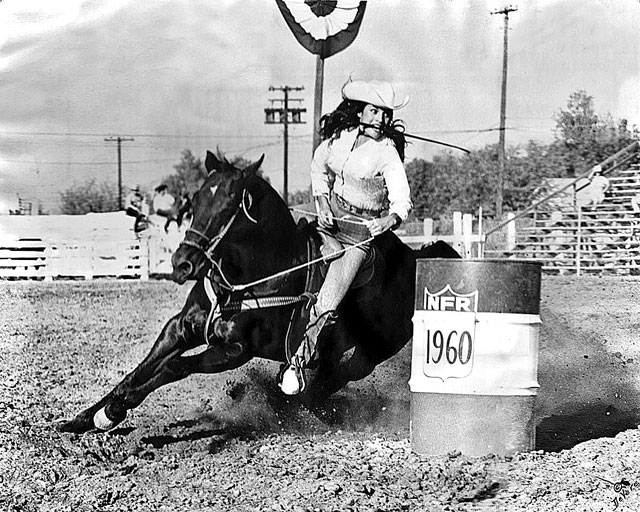

At the age of 27, she ran barrels at her first of what would be eleven consecutive National Finals Rodeos, and five years later, she was the world champion barrel racer.

She even doubled famous movie stars in the industry, doing horse riding and other stunts for them.

She was born in 1933 on a ranch in the Big Sandy, near Wickieup, Ariz., the daughter of Sam and Mamie Fancher. Her mother had three children from a previous marriage, but they were grown and out of the house. Named after her dad, he wanted a boy and treated her like one. “I did everything a boy would do,” she said.

Her father ran a ranch in Arizona, and when she was five years old, he quit his job to rodeo. The family moved to California to be closer to rodeos, since there weren’t a lot in Nevada at the time. After Sammy’s dad’s horse was injured, the family packed up again, this time moving near Imlay, Nevada, to work on another ranch. Her dad had bought interest in the ranch and rodeoed again to help pay the bills, and the mustangs Sammy broke were sold as kids’ ponies, which brought in a bit more income for the family.

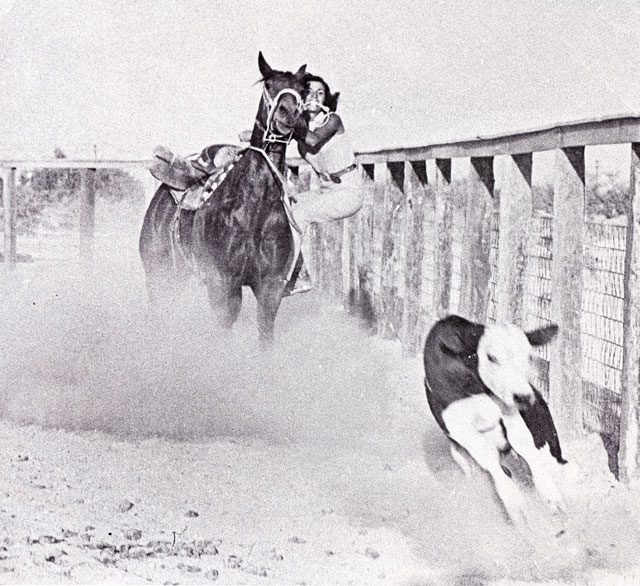

She attended rodeos with her dad, but few of them included women’s barrel racing. Barrel racing hadn’t found its way to California yet; it was more common in Oklahoma and Texas. She match raced, riding her dad’s horses, and rode calves, and read all she could about the Girls Rodeo Association, the forerunner to the Women’s Pro Rodeo Association.

By this time, the family was living near Las Vegas, Nev., and Sammy was sixteen. Every horse her dad had she turned into a barrel horse. One fall, she and her cousin tried to convince the organizers of a small rodeo in Las Vegas to add barrel racing. They talked them into it, and the first year, with forty entries, Sammy won first and her cousin won second.

By about 1950, a California rodeo advertised it was adding barrel racing, and Sammy went there, excited to run. But when she got there, there was no barrels; it was poles. She rode her barrel horse, having to “rein him through” the pattern. The girl who promoted the pole bending won the event. Sammy got even; on the second run, she got her dad’s rope horse: “you could do anything on him,” she said, “and he smoked the poles and I won the second round.”

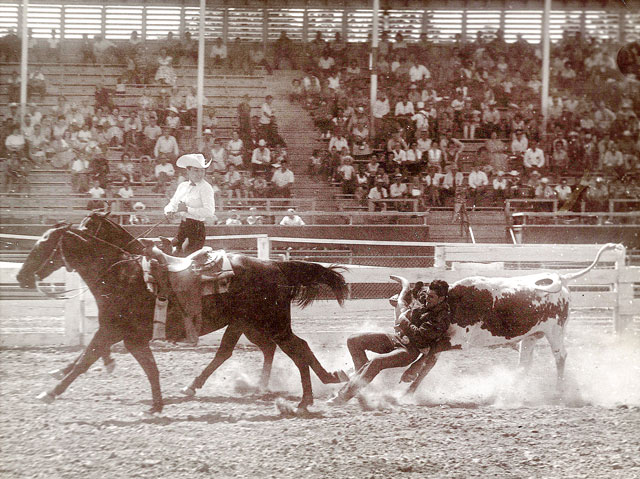

Sammy’s life was full of training horses, running barrels, and roping with her dad. Her first time competing with him at an RCA rodeo came about by accident. His partner didn’t show up, so she took his place. She hadn’t dally roped much, and her dad “was as nervous as a whore in church,” she laughed, about his daughter. “I got out perfect, laid it on (the steer),” Sammy said, “and when I roped him, my dad was looking at me to see if I was getting my dally, and went right on past the steer.”

Her daddy spoiled her, she said. One time, at a rodeo in Delano, Calif., she ran her rope horse in the barrels. When it was announced she’d have to run again because they missed her time, she told her dad she was going to ride Punkin, an exceptional palomino that her father used for the hazing, bulldogging, heading, heeling and calf roping. “No, you’re not,” he told her, and she replied, hide and watch! “I was a brat,” she laughed.

At the time, women were not allowed to compete in RCA rodeos, but Sammy and her dad were friends with Bill Linderman, RCA secretary and former president.

Linderman helped Sammy out several times, paving the way for her to rope with her dad. Bill told her, “when you want to enter, you tell them I said you could enter. If they give you grief, have them call me. So I started roping with my dad,” she said.

Because she did so well in the barrel racing, the Utah and Idaho rodeos often barred her from entering. She’d call on her friend Linderman again, and he’d say, “you tell them if they won’t let you enter, they can’t have barrels at the rodeo,” she remembered.

By then, barrel racing was becoming more common and more rodeos were including it. It helped, Sammy said, that world champion Wanda Bush and Florence Youree came to California to promote the event.

In 1960, she qualified for her first National Finals Rodeo. Living in Nevada, she competed in her home state and across California, Utah and Idaho. She and her dad made all the horses she rode, including what she considers her best horse, a bay mare named Ugh “because she was ugly,” Sammy remembers. The first time she had a chance to buy the mare, who wasn’t papered, the cost was $350. Her husband at the time, Anson Thurman, wouldn’t let her buy the horse. By the time she got her, the price was $850. But Ugh was worth it. “She was an outstanding barrel horse. You could do anything on her.”

Sammy qualified for the NFR every year from 1960-1970, winning the world in 1965. That year, she rode Ugh for most of the season but due to injury, the horse was out for the NFR. She rode a borrowed horse, Roanie and still finished third in the average. Sammy didn’t often rodeo back east; it was too far. But when she did, she borrowed horses, to cut down on the expense of driving a horse trailer and because the rodeos didn’t pay well enough to haul a horse.

One of the more innovative things she did for the sport was switching hands between the first and second barrel. Her dad taught her that. While most barrel racers ran with one hand, leading to the neck rein making horses stiff in the turn, Sammy changed hands between the first and second barrels. “Left hand, left turn, right hand, right turn,” she would chant to the students she later taught at clinics.

Sammy won rodeos all over: Rodeo Salinas (Calif.) several times; the Grand National at the Cow Palace in San Francisco; Phoenix; Red Bluff; Oakdale; Redding; Tucson; Denver; and Caldwell, among others.

In the mid 1960s, she began hosting barrel racing clinics. The concept was relatively new; Wanda Bush and Florence and Dale Youree had done some, and so had horse trainer Monte Forman, after whose she patterned hers. Barrel racing was so new that many of her students had only seen the event on TV.

They were three days in length, with the first day for observation. “I’d give (the students) a paper to fill out, a brief story on them and their horse. Then I’d watch them all make a run and analyze their runs,” she said. On day two, Sammy worked with each girl on any problems they might have, and the third day was competition, for students to put into practice what they had learned. She did the clinics for ten years.Another part of her life was doing stunt work in Hollywood. When she was eighteen, she had a part in the movie In Cold Blood. Then movie work was put on the back burner to rodeo, but after she married husband Bill Burton, a team roper, steer wrestler, bull rider, and stuntman, she became involved in movies again. In addition to horse riding, she did whatever stunts were needed, including swimming, even though she couldn’t swim. In the 1993 movie Another Stakeout, she had to jump off the dock into the Fraser River in Vancouver. “I told them I couldn’t swim,” she said, “and they had security guys all over to keep me safe.” After jumping in and coming up, she swam for the ladder. The safety man said, “I thought she can’t swim,’ and she told him, “I can sure swim when I need to,” she laughed.

She doubled for well-known actresses like Kathy Bates, Linda Evans, Jane Fonda and Dolly Parton. She was a charter member of the United Stuntwomen’s Association.

She also held positions in the GRA, serving as west coast director in the early 1970s and director at large. In 1975, she was voted president of the GRA, but didn’t stay in that role for long. Her new marriage to Burton and her work with the picture business kept her busy.

Sammy ran at her last pro rodeo in 1990, the same year she married her seventh husband, Jesse Brackenbury, a reined cow horse trainer, “possibly the best horse trainer I know,” Sammy said. She had her first daughter, Patti Parker, “before I was born,” she quips, joking about her age. She has two other daughters, Jodi Branco and Syd Thurman. Two of Jodi’s children, Stan Branco and Roy Branco, have continued the rodeo tradition. Stan, a steer wrestler, competed at the 2013 NFR and Roy has qualified for the California Circuit Finals in the tie-down roping. Her step-children include Billy Burton, Jr., David Burton, and Heather Gibson-Burton, along with six grandkids and four great-grandkids.

Thurman was inducted into the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame in August of 2019 and is a member of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Rodeo Hall of Fame. She has also been honored with the 2013 WPRA California Circuit True Grit award and the WPRA California Circuit Pioneer Cowgirl award in 2016.

The best part of her life, she says, started “when I was one year old and it’s still happening. I love my life, I love everything that’s happened in my life. I worked the picture business, I rodeoed, I loved it all and I still do.”